HISTORY YOU NEVER KNEW: The Other Popes In The Room

Francis Is Not The First Pontiff Buried in Historic Rome Basilica

The world watched this past weekend as Pope Francis, who died last Monday after leading the Roman Catholic Church for 12 years, was laid to rest at the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome. It surprised many when it was announced shortly after his death that Francis would not be buried in St. Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican, where most popes, including the first, St. Peter, are entombed.

Francis, who has never been known for being a fan of papal tradition, chose the basilica for his burial spot because of his devotion to Jesus’ mother. Santa Maria Maggiore is one of Rome's four major papal basilicas1 and the largest church in Italy dedicated to the Virgin Mary. He often visited the basilica as pope, including the day after his 2013 election, to pray to the Salus Populi Romani –Protectress of the Roman People – a sixth-century image of the Virgin Mary holding Jesus as a child. Francis’ tomb is just to the right of the chapel where the image is located.

Though Francis is the first pope in 122 years to be buried outside the Vatican, he is far from being one of the few. Dozens of popes are buried elsewhere in Rome and across Europe, with some laid to rest as far away from the Vatican as France and Germany. The Archbasilica of Saint John Lateran, which serves as Rome’s official cathedral, is home to numerous papal tombs, including that of Leo XIII, the last pontiff to be buried outside the Vatican. He was interred there in 1903.

The Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore is the final resting place for eight popes, including Francis. The church itself dates back to the days of the Roman Empire. According to legend, in the 4th Century AD, just a few decades after Emperor Constantine made Christianity the Empire’s official religion, a barren couple offered all their worldly goods to the Virgin Mary in exchange for a child. They asked for a sign from Mary that she heard their prayers, and on August 5, the height of the Roman summer, snow fell on Esquiline Hill, one of the seven hills of Rome. The pope at the time, Pope Liberius, recognized the miracle and decided to build a church in honor of the Virgin Mary on the hill, tracing the floor plan in the snow. The Catholic feast of Our Lady Of The Snows originates from this event, which marks the anniversary of the basilica’s dedication on August 5, 434 AD, approximately eight decades after the legend is dated. Historically, the basilica has also been known as the Basilica of Our Lady Of The Snows.

The basilica has undergone renovation and expansion over the centuries. It was rebuilt after an earthquake severely damaged it in the 14th century, and had a major reconstruction in the 18th Century. Still, the basilica’s central nave resembles its appearance when it was first constructed in the Fourth Century, in the design of the pagan basilicas of the Roman Empire.

Besides Francis, the seven other popes buried in the basilica reigned during notable events in world history. Five of the eight popes were interred there in the 16th and 17th centuries. Here is a list of them.

POPE HONORIUS III (1150-1227)

Reigned 1216-1227

A native Roman, Honorius was elected in a strange conclave in 1216. The 17 cardinals tasked with electing the pope handed the power over to a committee comprising just two. The duo chose Honorius after a one-day conclave in Perugia, two days after the previous pope died.

Honorius donned the papal tiara less than a year after King John of England was forced to sign the Magna Carta, the first significant restriction on a monarch’s power. Honorius’ predecessor, Innocent III, a supporter of John’s, declared the Magna Carta illegitimate, but Honorius played a significant role in its survival. John died just a few weeks into Honorius’ reign, leaving his nine-year-old son Henry III as king. As a child, Henry was under the control of regents his father had appointed, who sought to claw back regnal power from the nobility. This ultimately ended with a conflict that Henry nearly lost. In 1223, Honorius declared the seventeen-year-old Henry of legal age, allowing him to reissue the Magna Carta to end the conflict with English barons.

His nine years as head of the church coincided with the Fifth Crusade, which ended in a massive defeat for the Christians in Egypt in 1221. The defeat was blamed on Honorius’ nemesis, Frederick II, the Holy Roman Emperor. Politically, Honorius spent much of his reign battling Frederick, regularly siding with the French kings in their disputes with the emperor, including in the capture of Avignon by the French in 1226. Honorius also continued the persecution of the Cathars, a group of renegade Christians accused of heresy, in France.

Honorius reigned as pope during a time when two of the Catholic Church’s most well-known saints—Saint Dominic de Guzman and Saint Francis of Assisi2—were living and preaching. He approved the orders they formed, which are still major forces in the Catholic Church today: the Dominicans and the Franciscans.

Honorius was widely regarded as a kind ruler at a time when many popes were known for their tyrannical behavior. He died in 1227 and was buried at Santa Maria Maggiore; however, the location of his tomb has been lost, likely due to the earthquake that damaged the basilica in 1346, which may have destroyed it.

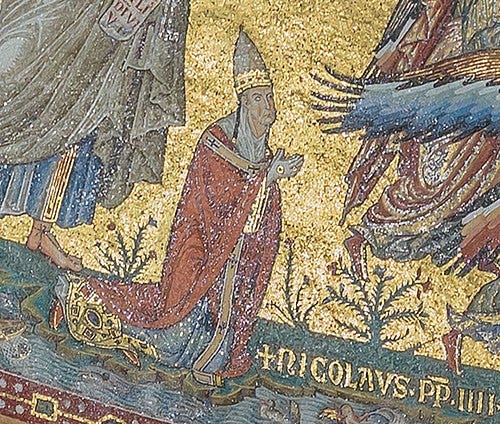

POPE NICHOLAS IV (1227-1292)

Reigned 1288-1292

While Honorius III approved the formation of the Franciscan order, the next pope to be buried at Santa Maria Maggiore was the first from the order to ascend to the papacy. Nicholas IV was born just a few months after Honorius died. He reigned for just four years, but oversaw one key reform to Church politics.

Nicholas allowed the cardinals to participate in the financial management of the Holy See, the governing body of the Vatican, and to receive half of the income, which gave them a level of independence that was later vital in their role in choosing the pope. The current structure of the College of Cardinals, which will choose Francis’ successor next month, stems from Nicholas IV.

As popes regularly did in this era, Nicholas IV played a role in a succession crisis. When the throne of Sicily was contested, Nicholas used his papal authority to hand the crown of Sicily to the French, rather than to the Spanish king of Aragon, igniting a political firestorm between Spanish and French interests in Italy that continued for centuries.

Nicholas’ most significant legacy was sending Christian missionaries to evangelize territories outside of the Mediterranean region, including Ethiopia and China, where Marco Polo was traveling during his reign. Nicholas is also remembered as the pope who commissioned the first Nativity scene.

Like Francis, Nicholas died close to Easter, on Good Friday, 1292, at a palace he had built next to Santa Maria Maggiore, and was buried in the basilica. His tomb was relocated to the northern wall, next to the main entrance, after a massive reconstruction of the church in the 18th Century.

POPE ST. PIUS V (1504-1572)

Reigned 1566-1572

Perhaps the most famous historical pope to be buried at Santa Maria Maggiore is St. Pius V, a member of the Dominican order, who reigned for six years between 1566 and 1572 during a pivotal time in Christian history.

He was not initially expected to become pope. Cardinal Alessandro Farnese, grandson of Pope Paul III and a member of the powerful Farnese dynasty, was seen as a lock to win the 1566 conclave. However, rumors reached Rome that Pius, then Michele Ghislieri, was favored by King Philip II of Spain, the most powerful Catholic monarch in Europe at the time. Ghislieri was known for his anti-establishment and anti-Protestant views.

Philip’s perceived endorsement and the support of future Saint Charles Borromeo, the Archbishop of Milan and a powerful Vatican insider, helped swing the election to Ghislieri, who took the name Pius V.

Pius was known for enforcing a higher standard of morality among the clergy, a response to criticism of corruption and flagrancy that helped spark the Protestant Reformation. He is also considered the father of the Traditional Latin Mass.

Pius was integral in two of the most important historical events of the 16th Century. He authored the papal bull Regnans in Exclesis, which excommunicated Queen Elizabeth I of England. This set the stage for a Catholic uprising that led to the Spanish Armada and attempts to overthrow her and replace her with a Catholic monarch. He was also a strong supporter of Elizabeth’s rival and cousin, Mary, Queen of Scots.

Pius also coordinated the Holy League’s buildup of naval forces to counter the mighty Ottoman Empire's navy, which threatened Western Europe. In 1571, during Pius’ reign, the Holy League destroyed the Turkish Navy at the Battle of Lepanto in Greece. The victory marked a significant turning point in the conflict between Europeans and Turks, ultimately saving much of Europe from the threat of further Islamic expansion. A battle fresco hangs today in the Vatican Museum’s Gallery of Maps.

Pius died in 1572 and was buried in an elaborate tomb in Santa Maria Maggiore’s Sistine Chapel. As is common with Catholic saints, his body is still visible through a glass sarcophagus.

POPE SIXTUS V (1521-1590)

Reigned 1585-1590

When Pope Sixtus V was elected in 1585, he inherited a Rome in crisis. The city was beset by lawlessness, and disease ran rampant. Sixtus’ papacy is not known as much for his policies on religion, but rather for his focus on social order and infrastructure policies. It was under his reign that the city of Rome, as we know it, came to fruition.

Sixtus laid out the grand avenues Rome is known for today, connecting the city’s major basilicas and piazzas. He constructed new aqueducts to funnel water to dozens of city fountains. The dome of St. Peter’s Basilica was completed during his reign. He also brutally cracked down on criminal activity in the city, earning him a reputation as a tyrant.

Sixtus was pope when Queen Elizabeth I of England had Mary, Queen of Scots executed, and King Philip II sent the Spanish Armada to invade England to restore Catholicism to the country. Mary had written to Sixtus several months before her execution, pleading with him to intercede and save her life, but he ignored her pleas. However, he reaffirmed Pius V’s excommunication of Elizabeth I after Mary’s execution, which Philip saw as an endorsement of his campaign to invade England and dethrone Elizabeth. Although Sixtus supported the Spanish Armada financially, he refused to offer more support until Spanish troops successfully landed in England and overthrew Elizabeth. Some historians see Sixtus’s lack of encouragement and support for the Armada as a significant factor in its failure.

Sixtus is the only pope to have excommunicated the monarchs of both England and France. He excommunicated King Henri of Navarre, the heir to the French throne, in a vain attempt to prevent the sometimes-Protestant king from inheriting the crown. Henri became King of France in 1589, and though he publicly professed to be a Catholic, he was known for harboring Protestant views.

In his short reign, Sixtus only canonized one saint – Didacus of Alcalá, also known by his Spanish name, Diego. He is the namesake of the city of San Diego, California.

Sixtus died of malaria in 1590 and was buried not far from Pius V, who had died just 18 years earlier, in Santa Maria Maggiore’s Sistine Chapel.

POPE CLEMENT VIII (1536-1605)

Reigned 1592-1605

Pope Clement VIII is a controversial figure in the history of the papacy. He was elected in the fourth papal conclave held over the three years after the death of Sixtus V, which led to three extremely short papacies between Sixtus and Clement.

Known for being a tough administrator, Clement VIII restored the relationship between Rome and King Henri of France, rescinding Sixtus’ excommunication. He also negotiated a key peace treaty between France and Spain. Clement helped muster support from both powers to fight the Ottomans in Eastern Europe, thereby preventing them from making another attempt at invading Western Europe.

Clement VIII is perhaps best known for his persecution of Jews in the Papal States and for overseeing two of the most infamous trials in church history - those of Beatrice Cenci and Giordano Bruno, both of which occurred within six months of each other.

Cenci, her brother, and stepmother were tried and brutally executed in September 1599 for the murder of Cenci’s father, Francesco, an influential member of Rome’s nobility. The family plotted Francesco’s murder after years of rape and abuse that went ignored by the Roman elit. Beatrice and her family’s trial and execution caused a public uproar in Rome, and Cenci’s story has inspired numerous operas and songs.

Bruno, a scientist and cosmologist, gained fame for his theories about the stars and planets. Clement VIII feared the popularity of his teachings, which contradicted some of the Church's teachings. Bruno was tried for heresy and burned at the stake in the Campo de’ Fiori in February 1600. A statue of a solemn Bruno in a hood stands at the site of his execution today.

Though this story is sometimes considered a legend, Clement VIII is often credited with popularizing coffee as a beverage in the Christian world. Initially thought of as an evil beverage, Clement loved it so much that he allegedly blessed the coffee bean, officially sanctioning it for consumption by Catholics.

Clement died in 1605 and was initially buried in St. Peter’s Basilica before being moved in 1646 to a tomb constructed 25 years earlier by his protege, Pope Paul V, in the newly built Borghese Chapel of Santa Maria Maggiore. Today, the chapel is where the Salus Populi Romani image is located, and his tomb is only steps from Pope Francis’ grave.

POPE PAUL V (1550-1621)

Reigned 1605-1621

When Pope Clement VIII died in 1605, the election to replace him turned into – forgive the phrase but it best describes it – a complete shitshow.

The conclave was held in March and April 1605. Cardinal Caesar Baronius, a popular orator and historian well-liked in the Vatican, was the odds-on favorite to win the papacy. The only problem was King Philip III of Spain, who disliked Baronius due to his support for papal claims to the throne of Sicily, a Spanish territory. Kings still had some veto power over the election of the papacy, and Philip refused to let Baronius win.

The result was a deadlocked conclave that finally elected Alessandro di Ottaviano de' Medici, a relative of Marie de Medici, the queen consort of France and wife of Henri IV, whose excommunication Clement VIII had rescinded. The Spanish representatives at the conclave protested loudly, leading to a shouting match in the Vatican, but the election was upheld. Medici took the name Leo IX and promptly made everything more complicated by dying a month later.

It’s May 1605, and the cardinals are back in conclave again. Among those considered for the papacy in that conclave was future Saint Robert Bellarmine. This election turned violent when the debate led to a physical altercation between the cardinals in the conclave. One cardinal suffered broken bones. Ultimately, Pope Paul V was elected as a compromise candidate. At only 54, he was atypically young for a pope.

Paul’s reign is most notable for being the era during which astronomer Galileo Galilei lived. Paul supported Galileo but warned him not to push the Copernican theory, which posits that the Earth revolves around the sun. Galileo refused and fell out with Paul, who turned him over to the Inquisitors.

Other notable events during Paul’s reign included the Venetian Interdict, a conflict with the city-state of Venice over whether the city’s government or the Pope had jurisdiction over the clergy in Venice. The defiance of the Venetian Doge and his government led Paul to excommunicate the entire city government.

During Paul’s reign, the Vatican established diplomatic relations with Japan. After a decade of brutal suppression of Christianity in Japan, Paul welcomed samurai Hasekura Tsunenaga to Rome as an ambassador and helped coordinate trade agreements between Japan and Spain. He also sought protection for Christians in Japan.

Paul died in 1621 and was buried near Clement VIII in the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore.

POPE CLEMENT IX (1600-1669)

Reigned 1667-1669

Pope Clement IX had a very short reign, less than two years. His election was dominated by the influence of the “Flying Squad,” a group of liberal cardinals supported by exiled Queen Christina of Sweden, a Catholic convert, that sought to elect reformist cardinals to the papacy and supported candidates not backed by Europe’s monarchs. For centuries, Europe’s Catholic monarchs exerted significant influence over the election of popes. A native of Tuscany, Clement’s election was also supported by the monarchs of France and Spain, who took advantage of the split in the Flying Squad. This helped avoid the conflicts that had plagued the elections of his predecessors and advanced the liberals’ cause of curtailing nepotism. Two nephews of two previous popes were excluded from being elected by the conclave, which accepted Clement as a compromise.

Clement, a patron of the arts, had a close relationship with the Italian sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini3. During Clement’s short reign, Bernini was commissioned to construct the colonnade that encircles the piazza in St. Peter’s Square and the sculptures of angels that adorn the Ponte Sant’Angelo. This bridge connects the center of Rome to the Vatican over the Tiber River. Clement also constructed the first public opera house in Rome.

Clement died weeks after the Venetians lost the island of Crete to the Ottomans, allegedly broken by the defeat. Much like Francis and unlike most popes of his day, Clement was known for humility. He often heard confessions of everyday Romans in the confessionals at St. Peter.

He was buried in a simple tomb under the floor at Santa Maria Maggiore, but his successor, Clement X, built him a more ornate tomb that still exists on the right side of the nave.

The other three are St. Peter at the Vatican, St. John Lateran, Rome’s official cathedral and the seat of the Bishop of Rome, a title held by the Pope, and St. Paul Outside the Walls, where St. Paul the Apostle is buried.

As my birth name is Domenick Francis, I am highly familiar with these two namesake saints.

Bernini is also buried at Santa Maria Maggiore.