Democrats Must Sit Down, Be Humble

Liberals' Bad Reputation Undermines Whatever Popular Policies They Offer

“If you don’t know we’re better, you’re stupid. That’s our message.”

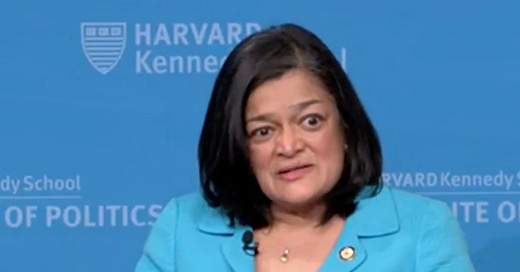

Last week, at a symposium at Harvard University, Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-Washington), the former chair of the Congressional Progressive Caucus, said that is what Trump supporters and apathetic voters hear from Democrats, and that’s why their messaging does not work. Her comments got a lot of attention on social media, specifically regarding the reputation of people on the left for being smug, arrogant, and dismissive of voters who disagree with them.

Jayapal correctly identifies a problem often talked about and widely accepted, but it led to a crossfire of blame and accountability over which faction of the Democratic coalition is responsible. Progressives point out that Democratic economic policies are popular, but the party is not. They believe it is because of moderates and neoliberals who don’t emphasize these policies, but progressives do even worse electorally than moderates. They quickly point out that Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vermont) has high favorability ratings. Still, he could not win two presidential primaries, and the candidates he backed nationally only ever won in left-wing urban districts, and even then, their track records were mixed. Jayapal speaks of arrogance and smugness, but this is not just a neoliberal problem. It’s a problem that is endemic to progressives – and let me rankle people in suggesting that it’s worse for progressives because not only are they smug and arrogant, but they do not know how to relate socially or culturally to the communities they want to represent. Here’s an interesting story to illustrate that:

In 2021, Democrats united behind a candidate in my City Council district, where Joe Biden won by 16 points the year before. Left-wing groups like Democratic Socialists of America and establishment leaders like Sen. Chuck Schumer (D-New York), who represented the area in the U.S. House of Representatives in the 1990s, both lined up behind the Democratic nominee, Felicia Singh, a schoolteacher and daughter of a cab driver.

Singh’s supporters contacted me early in the campaign, wanting some insight into the district. It was Republican-held, and Democrats hoped to pick it up as an open seat. I had covered it for over a decade as a local reporter and had some experience with the district’s politics.

In 2009, while helping out on the unsuccessful campaign1 of the Democratic frontrunner in the same district, I interviewed voters. To my surprise, among the most dominant campaign issues - remember this was among Democratic voters in a City Council race - was frustration that newly-elected President Barack Obama was banning the use of torture in interrogating terror suspects. The 9/11 attacks had severely affected the district, and Bush-era anti-terror policies were popular among the working class and middle class here. One voter asked me where the Democratic candidate stood on that issue because “they would do it to our guys.” Again, this was a local City Council race.

Rather than get combative on the issue—I was utterly disgusted by some of the voters’ takes on it—the campaign advised that we smile, acknowledge the concern, and not argue with voters about it. Progressives working on Singh’s campaign, talking to many of the same voters 12 years later, did the opposite.

Some campaign workers told me they believed Singh would win because "she's likable" and her opponent, now Councilwoman Joann Ariola, was not. Ariola was a divisive figure in the neighborhood. She had seized control of the floundering Howard Beach Civic Association in one of New York’s most conservative communities just weeks into Mayor Bill de Blasio’s first term. It was a controversial coup where she highlighted a string of local burglaries that cops were later unable to solve – and NYPD sources later told me off the record they believed never happened. She had lost two previous elections earlier, including one for the same seat in 2001. The politics of the district, however, had shifted by 2021.

At the end of the campaign, when it became clear that Singh would lose, she was canvassing my block and met with a neighbor of mine, a lifelong Democrat who probably hadn't voted that way since before 9/11. He was a contractor with an AFL-CIO sticker on his truck, who had built his business from the ground up and was environmentally conscious, using well water in his house and growing his own food in his yard.

He was also an elderly Italian-American man who had fallen madly in love with Donald Trump. When Singh came to ask for his vote, he scolded her, saying that he wouldn't vote for a Democrat because Biden had "ruined him." He complained about his portfolio being down (it wasn't) and about “out-of-control crime.”

At the end of the exchange, he told Singh that he liked her and respected her as a teacher. This exchange was reported in a local paper shadowing her campaign. He then voted for Ariola anyway. Later, one of Singh's campaign aides asked me, "How can he like her and not Joann and still vote for Joann? I don't get it."

I had to explain, to no avail, that it wasn't primarily about Singh; it was about what she represented and what kind of movement surrounded her. The neighbor she spoke to had told another neighbor that one of his reasons for not voting for Singh was her ethnicity, and he was angry that "her people took over.2" She didn't care that she was pro-union or supporting the "working class" because he said, "her ideas aren't for us, they're for her people."

I also explained that her campaign volunteers largely came from outside the district, mainly from gentrified parts of Brooklyn, and did not look like the voters in the neighborhood. The campaign had a canvasser on my friend's block – a college-aged woman with pink hair and unshaven armpits. My friend’s neighbors made fun of her at a community meeting a while later, telling him, "If you want to win our votes, tell them to send normal people." Campaign staff did not like me bringing this up and suggested it was “misogynist” or “homophobic,” and immediately dismissed these concerns. I get it; much of the progressive movement in New York City and nationally is dominated by young people who make a concerted effort not to conform. They dress differently and refuse to follow common customs and expectations. That’s fine, but when you’re trying to connect to communities like mine, being a non-conformist does not work. It’s an immediate red flag and seen as a threat to the culture of the working class, and middle-class people feel threatened. This is true in working-class communities all across America.

Some campaign staff got combative with neighbors of mine who argued they wanted stricter enforcement of noise laws; they wanted a homeless shelter closed, and they wanted police walking the beat. Campaign volunteers suggested those issues were “fabricated” and that people were being “brainwashed” into thinking they were problems by the media. As a prop, the campaign marched in the district with an oversized cardboard cutout of Singh’s head, which several neighbors and voters said they found “creepy” and “weird.”

It didn't matter that Singh personally appealed to many of these people; her message was wholly out of touch with this part of the city. The campaign came across as disconnected, and the response to some of voters’ conservative-coded priorities was dismissive and arrogant.

So, how does this relate to Bernie?

Like Singh, Bernie is likable, but many who would say nice things about him would never vote for him or anyone he backs. They don't like or feel welcomed in the political and social culture formulated around Bernie’s movement. They see it as out of touch, smug, elitist, and weird. They don't trust it. It doesn’t matter if his ideas are liked; most voters, like those in my neighborhood, believe his movement would not prioritize them over other groups. That's why he hasn't been able to convert his popularity into votes, and that's what's hurting the Democratic Party now.

The progressives who supported Singh's campaign got bitterly angry and combative with me when I told them these seemingly meaningless things—a non-white candidate, armpit hair canvasser, calling people Karens for wanting to enforce noise regulations—hurt her. I got called every name in the book. Still, I remain steadfast in stating that they harmed the campaign and the movement. In 2024, Trump won the council district by nine, a 25-point swing from 2020.

Like Singh, Bernie is likable, but many who would say nice things about him would never vote for him or anyone he backs because they don't like or feel welcomed in the political and social culture formulated around him.

This “smugness” and “arrogance” was not limited to progressives, especially post-2016. Mainstream liberals can also come across this way. It isn’t a new thing. Liberals were accused of being smug during the Clinton years. It was often a topic in The West Wing. I remember some conservative and moderate friends cringing about how “arrogant” the now-iconic Jeff Daniels monologue in The Newsroom3 was to them. During the COVID-19 Pandemic, this type of arrogance was coming from all factions of the Democratic bloc. While leftists were the loudest in accusing people of being bigots for not wearing masks, getting vaccinated, or staying home and bizarrely decided to go to war with brunch, liberals were happy enough, especially early on, to parrot that message and accuse any critic of COVID-19 mitigation policies of “not following the science,” even as we now fully understand that science had more holes in it than Clyde Barrow’s car.

The smugness around COVID-19 was just an extension of the larger canceling culture that irked people during the 2010s. This stemmed from complacency after Obama’s wins in 2008 and 2012. These election victories may have convinced the entire Democratic coalition that total victory was inevitable and there was no reason for humility. Meanwhile, in 2009, when I was told to be humble, we were still in the shadow of the post-9/11 erasure of liberals from society in a city where Democrats hadn’t won the mayor’s office in 20 years.

Perhaps another lesson in humility has been needed since 2020, and Trump’s 2024 election was that. Jayapal’s concession seems to imply it.

The candidate, Frank Gulluscio, was expected to win the seat vacated by State Sen. Joe Addabbo reasonably easily. He was tossed off the ballot on a technical issue, and Republican Eric Ulrich won it and held it until 2021.

My neighborhood, long dominated by Italian-Americans and Irish-Americans, had become largely South Asian and Indo-Caribbean since the 1990s, and Singh was from that community.

Ironically, Will McAvoy, Daniels’ character, was written as a disaffected moderate Republican, something that also pissed off some conservatives in my social circle at the time.

Alright then explain Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez's unique appeal. Granted, were she to run for Senate or Presidency, it's still unclear whether AOC would be accepted by enough of the country to win. But she has an "it" factor that's clearly striking a chord with mainstream Democrats on top of progressives, something even Sanders never managed. Maybe it's because AOC knows how to speak digital media better than any Dem, even those her age in Washington right now, but there's something about her that works.