Congestion Pricing Goes Down (For Now)

Thank Arrogance, Political Ignorance And Incoherent Messaging From Supporters

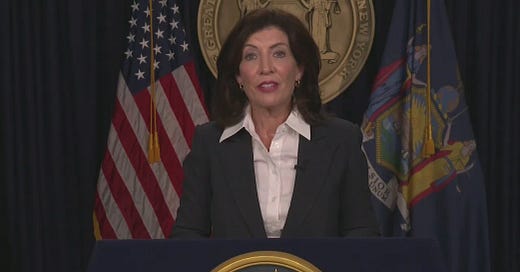

New York Gov. Kathy Hochul abruptly and unilaterally postponed, potentially indefinitely, the implementation of the Congestion Pricing program in Manhattan, sending political shockwaves through her state.

Like the plans implemented in London, Paris, and Singapor…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Nick Rafter Writes to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.